The Full Web Version of this book

as well as links to other available ebooks

and some printed versions of them, quotes from

the book, and other links can be found at:

INQUIRIES are continually being made for a brief, clear and dispassionate history of the Revolution of 1893 and of the events that led up to it. The lapse of time has already moderated the bitterness of party spirit, and made it possible to form a juster estimate of the chief actors on both sides of that controversy.

A brief sketch of the salient political events of 1887, was written for Col. J. H. Blount at his own request, and afterwards republished by the Hawaiian Gazette Co. At their request the writer reluctantly consented to continue his sketch through Kalakaua's reign and that of Liliuokalani until the eve of the Revolution of 1893, and afterwards to draw up a more detailed account of the revolution and of the subsequent events of that year. The testimony of the principal witnesses on both sides has been carefully sifted and compared, and no pains has been spared to arrive at the truth.

Much assistance has been derived from a paper by the Rev. S. E. Bishop covering the latter part of the period in question, and Chapter VI stands as he wrote it with some slight alterations.

The writer, while not professing to be a neutral, has honestly striven not "to extenuate aught or set down aught in malice," but to state the facts as nearly as possible, in their true relations and in their just proportions. The official documents on both sides bearing on the case are given in full, including the report of Col. J. H. Blount to the President of the United States, and the report of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, drawn up by Senator Morgan of Alabama.

William DeWitt Alexander,

CHAPTER I

PERSONAL GOVERNMENT.

Intrigues during Lunalilo's Reign — Election of Kalakaua — Court House Riot — Inauguration of Kalakaua — Advent of Col. Spreckels — Celso Caesar Moreno — Legislative Session of 1880 — Fall of the Moreno Ministry — The W. L. Green Cabinet — Kalakaua's Tour around the World — Triumph of Gibson — Legislature of 1882 — Coronation — Embassies — Hawaiian Coinage — Reconstruction of Gibson Cabinet — Legislature of 1884 — Spreckels' Banking Act — Lottery Bill, etc. — Practical Politics — Elections of 1886 — Opium License Bill — London Loan — Sequel to London Loan — Royal Misrule — The Hale Nana — Kalakaua's Jubilee — Embassy to Samoa — The Kaimiloa — The Aki Opium Scandal — Revolution of 1887 — Constitution of 1887. Pages 1-22

CHAPTER II

UNDER THE CONSTITUTION OF 1887.

The Question of the Royal Veto — Conspiracies — Proposed Commercial Treaty with the U. S. — Legislative Session of 1890 — Accession of Liliuokalani — Equal Rights League — Legislature of 1892 — Triumph of the Queen's Party. Pages 22-28

CHAPTER III

REVOLUTION OF 1893.

Return of the Boston — Warnings — The Prorogation Conference in the Foreign Office — Scenes in the Palace — Appeal to Citizens — Postponement of the Coup d'Etat — Features of the Queen's Constitution — Committee of Safety Organized — Interview with Stevens — Conference held Saturday Evening — Offer made to Colburn and Peterson — Second meeting of Committee of Safety — Proceedings of the Queen's Friends Sunday Afternoon — The Queen's Retraction — Third Meeting of Committee of Safety — Request for the Landing of U. S. Troops — Mass Meeting at the Armory — Report of Committee of Safety — Mass Meeting at Palace Square — Landing of U. S. Troops - Protests — Meeting of Committee of Safety Monday Evening — Mr. Damon's Interview with the Queen — Last Meeting of the Committee of Safety — Proceedings of the Queen's Party — Final Action of the Committee of Safety — The Shot fired on Fort Street — Proclamation of the Provisional Government — The Volunteers — Various Communications — Last Appeal by the Cabinet to Stevens — The Queen's Surrender — Surrender of the Station House and the Barracks — Recognition of the Provisional Government — Dispatch of Annexation Commissioners — The U. S. Protectorate. Pages 29—71

CHAPTER IV

NEGOTIATIONS AT WASHINGTON.

Treaty of Annexation — Mission of Hon. Paul Neumann — Mission of Mr. Davies and Princess Kaiulani — Withdrawal of the Treaty. Pages 71-79

CHAPTER V

THE MISSION OF COMMISSIONER BLOUNT.

Appointment of Commissioner Blount — His Arrival in Honolulu — The Hauling down of the U. S. Flag — Reception of Royalist Committees, etc. — The Bowen-Sewall Episode — Col. Blount's warning to American Citizens — The Nordhoff Libel Case — Col. Claus Spreckels' Demand — Conspiracies — Col. Blount's Investigations — His Report Pages 79-91

CHAPTER VI

PRESIDENT CLEVELAND'S ATTEMPT TO RESTORE THE QUEEN

Hon. A. S. Willis' Appointment and Instructions — His Arrival at Honolulu — Negotiations with the Ex-Queen — Mass Meeting at the Drill Shed — Arrival of the Corwin with fresh Instructions to Minister Willis — The President's Message — The "Black Week" in Honolulu — Minister Willis' renewed Interviews with the Queen — Mr. J. O. Carter's Mediation — The Demand for the Restoration of the Queen — President Dole's Reply to the Demand — President Dole's Letter of Specifications. Pages 91—134

Supplement A

Report of Col. J. H. Blount. Pages 135—167

Supplement B

Report of the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs. Pages 167—201

Chapter I

Rise and Fall of the Insurrection. Pages 203—208

Chapter II

Trial of Political Prisoners. Pages. 208—214

Chapter III

Abdication and Trial of Liliuokalani. Pages 215—222

Chapter IV

Landing of Arms and General Scheme of the Rebellion. Pages 222—224

Chapter V

Deportation of Political Exiles. Pages. 224—225

Chapter VI

Pardon of Political Prisoners. Pages 226—228

Chapter VII

Diplomatic Complications — Review. Pages 228—232

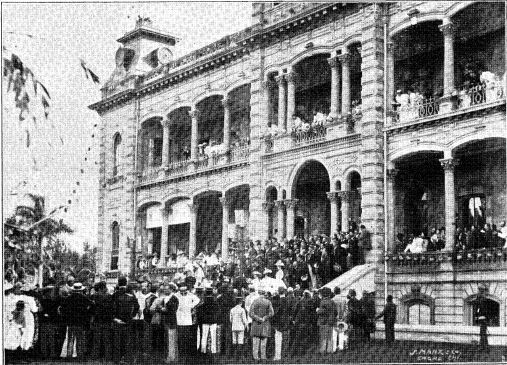

LIST OF lLLUSTRATIONS

Portrait of Kalakaua. Page 2

Ex-Queen Liliuokalani. Page 25

President S. B. Dole. Page 54

Proclamation of the Republic, July 4, 1894. Page 134

It is true that the germs of many of the evils of Kalakaua's reign may be traced to the reign of Kamehameha V. The reactionary policy of that monarch is well known. Under him the "recrudescence" of heathenism commenced, as evinced by the Pagan orgies at the funeral of his sister, Victoria Kamamahi, in June, 1866, and by his encouragement of the lascivious hulahula dancers and of the pernicious class of Kahunas or sorcerers. Closely connected with this reaction was a growing jealousy and hatred of foreigners.

INTRIGUES DURING LUNALILO'S REIGN.

During Lunalilo's brief reign, 1873-74, this feeling was fanned into a flame by several causes, viz., the execution of the law for the segregation of lepers, the agitation caused by the proposal to cede the use of Pearl Harbor to the United States, and the famous mutiny at the barracks. This disaffection was made the most of by Kalakaua, who was smarting under his defeat in the election of January, 8, 1873. Indeed, his manifesto previous to that election appealed to this race prejudice. Thus he promised, if elected, "to repeal the poll tax," "to put native Hawaiians into the Government offices," "to amend the Constitution of 1864," etc. "Beware," he said, "of the Constitution of 1852, and the false teaching of the foreigners, who are now seeking to obtain the direction of the Government, if Lunalilo ascends the throne." Walter Murray Gibson, formerly Mormon apostle and shepherd of Lanai, then professional politician and editor of that scurrilous p2 paper, the Nuhou, was bitterly disappointed that he had been ignored in the formation of Lunalilo's cabinet. Accordingly he took the role of an agitator and attached himself to Kalakaua's party. They were both disappointed at the result of the barracks mutiny, which had undoubtedly been fomented by Kalakaua.

THE ELECTION OF KALAKAUA.

Upon Lunalilo's untimely death, February 3, 1874, as no successor to the throne had been appointed, the Legislature was summoned to meet on the 12th, only nine days after his death. The popular choice lay between Kalakaua and the Queen-Dowager Emma. The Cabinet and the American party used all their influence in favor of the former, while the English favored Emma, who was devoted to their interest. At the same time Kalakaua's true character was not generally understood. The natives knew that his family had always been an idolatrous one. His reputed grandfather, Kamanawa, had been hanged, October 20, 1840, for poisoning his wife, Kamokuiki.

Under Kamehameha V. he had always been an advocate of absolutism, and also of legalizing the furnishing of alcoholic liquors to natives. While he was postmaster a defalcation occurred, which was covered up, while his friends made good the loss to the Government. Like Wilkins Micawber, he was impecunious all his life, whatever the amount of his income might be. He was characterized by a fondness for decorations and military show long before he was thought of as a possible candidate for the throne.

It was believed, however, that if Queen Emma should be elected there would be no hope of our obtaining a reciprocity treaty with the United States. The movement in favor of Queen Emma carried the day with the natives on Oahu, but had not time to spread to the other islands. It was charged, and generally believed that bribery was used by Kalakaua's friends to secure his election. Be that as it may, the Legislature was convened in the old court-house (now occupied by Hackfeld & Co.) and elected Kalakaua King by 39 votes to 6.

THE COURT-HOUSE RIOT.

A howling mob, composed of Queen Emma's partizans, had surrounded the court-house during the election, after which they battered down the back-doors, sacked the building, and assaulted the representatives with clubs. Messrs. C. C. Harris and S. B. Dole held the main door against them for considerable time. The mob, with one exception, refrained from violence to foreigners, from fear of intervention by the men-of-war in port.

The cabinet and the marshal had been warned of the danger, but had made light of it. The police appeared to be in sympathy with the populace, and the volunteers, for the same reason, would not turn out. Mr. H. A. Pierce, the American Minister, however, had anticipated the riot, and had agreed with Commander Belknap, of the U. S. S. Tuscarora, and p3 Commander Skerrett, of the Portsmouth, upon a signal for landing the troops under their command. At last Mr. C. R. Bishop, Minister of Foreign Affairs, formally applied to him and to Major Wodehouse, H. B. M.'s Commissioner, for assistance in putting down the riot.

A body of 150 marines immediately landed from the two American men-of-war, and in a few minutes was joined by seventy men from H. B. M.'s corvette Tenedos, Capt. Ray. They quickly dispersed the mob and arrested a number of them without any bloodshed. The British troops first occupied Queen Emma's grounds, arresting several of the ring-leaders there, and afterwards guarded the palace and barracks. The other Government buildings, the prison, etc., were guarded by American troops until the 20th.

INAUGURATION OF KALAKAUA.

The next day at noon Kalakaua was sworn in as King, under the protection of the United States troops. By an irony of fate the late leader of the anti-American agitation owed his life and his throne to American intervention, and for several years he depended upon the support of the foreign community. In these circumstances he did not venture to proclaim a new constitution (as in his inaugural speech he had said he intended to do), nor to disregard public opinion in his appointments. His first Minister ot Foreign Affairs was the late Hon. W. L. Green, an Englishman, universally respected for his integrity and ability, who held this office for nearly three years, and carried through the treaty of reciprocity in the teeth of bitter opposition.

THE RECIPROCITY TREATY.

The following October Messrs. E. H. Allen and H. A. P. Carter were sent to Washington to negotiate a treaty of reciprocity.

The Government of the United States having extended an invitation to the King, and placed the U. S. S. Benicia at his disposal, he embarked November 17, 1874, accompanied by Mr. H. A. Pierce and several other gentlemen. They were most cordially received and treated as guests of the nation. After a tour through the Northern States the royal party returned to Honolulu February 15, 1875, in the U. S. S. Pensacola. The treaty of reciprocity was concluded January 30, 1875, and the ratifications were exchanged at Washington June 3, 1875.

The act necessary to carry it into effect was not, however, passed by the Hawaiian Legislature till July 18, 1876, after the most stubborn opposition, chiefly from the English members of the house and the partisans of Queen Emma, who denounced it as a step toward annexation. It finally went into effect September 9, 1876.

THE ADVENT OF SPRECKELS.

The first effect of the reciprocity treaty was to cause a "boom" in sugar, which turned the heads of some of our p4 shrewdest men and nearly caused a financial crash. Among other enterprises the Haiku irrigation ditch, twenty miles in length, which taps certain streams flowing down the northern slopes of East Maui and waters three plantations, was planned and carried out by Mr. S. T. Alexander, in 1877. About that time he pointed out to Col. Claus Spreckels the fertile plain of Central Maui, then lying waste, which only needed irrigation to produce immense crops. Accordingly, in 1878, Mr. Spreckels applied to the cabinet for a lease of the surplus waters of the streams on the northeast side of Maui as far as Honomanu. They flow through a rugged district at present almost uninhabited. The then Attorney-General. Judge Hartwell, and the Minisister of the Interior, J. Mott Smith, refused to grant him a perpetual monopoly of this water, as they state it. Up to this time the changes in the cabinet had been caused by disagreements between its members, and had no political significance.

In the mean time, Mr. Gibson, after many months of preparation, had brought in before the Legislature a motion of want of confidence in the ministry, which was defeated June 24, by a vote of 26 to 19. On the night of July 1, Messrs. Claus Spreckels and G. W. Macfarlane had a long conference with Kalakaua at the Hawaiian Hotel on the subject of the water privilege, and adjourned to the palace about midnight. It is not necessary to give the details here, but the result was that letters were drawn up and signed by the King, addressed to each member of the cabinet, requesting his resignation, without stating any reason for his dismissal. These letters were delivered by a messenger between 1 and 2 o'clock in the morning. Such an arbitrary and despotic act was without precedent in Hawaiian history.

The next day a new cabinet was appointed, consisting of S. G. Wilder, Minister of the Interior; E. Preston, Attorney-General; Simon Kaai. Minister of Finance; and John Kapena, Minister of Foreign Affairs. The last two positions were sinecures, but Kaai as a speaker and politician had great influence with his countrymen. The new cabinet granted Mr. Spreckels the desired water privilege for thirty years at $500 per annum. The opium license and free liquor bills were killed. The actual premier, Mr. Wilder, was probably the ablest administrator that this country has ever had. He infused new vigor into every department of the Government, promoted immigration, carried out extensive public improvements, and at the legislative session of 1880 was able to show cash in the treasury sufficient to pay off the existing national debt. But his determination to administer his own department in accordance with business methods did not suit the King.

Meanwhile Gibson spared no pains to make himself conspicuous as the soi-disant champion of the aboriginal race. He even tried to capture the "missionaries," "experienced religion," held forth at sundry prayer meetings, and spoke in favor of temperance.

CELSO CAESAR MORENO.

The professional lobbyist, Celso Caesar Moreno, well known at Sacramento and Washington, arrived in Honolulu November 14, 1879, on the China Merchants' Steam Navigation Company's steamer Ho-chung, with the view of establishing a line of steamers between Honolulu and China. Soon afterwards he presented a memorial to the Hawaiian Government asking for a subsidy to the proposed line. He remained in Honolulu about ten months, during which time he gained unbounded influence over the King by servile flattery and by encouraging all his pet hobbies. He told him that he ought to be his own prime minister, and to fill all Government offices with native Hawaiians. He encouraged his craze for a ten-million loan, to be spent chiefly for military purposes, and told him that China was the "treasure house of the world," where he could borrow all the money he wanted. The King was always an active politician, and he left no stone unturned to carry the election of 1880. His candidates advocated a ten-million loan and unlimited Chinese immigration. With Moreno's assistance he produced a pamphlet in support of these views, entitled "A reply to ministerial utterances."

THE SESSION OF 1880.

In the Legislature of 1880 was seen the strange spectacle of the King working with a pair of unscrupulous adventurers to oust his own constitutional advisers, and introducing through his creatures a series of bills, which were generally defeated by the ministry.

Gibson had now thrown off the mask, and voted for every one of the King and Moreno's measure's. Among their bills which failed were the ten-million loan bill, the opium license bill, the free-liquor bill, and especially the bill guaranteeing a bonus of $1,000,000 in gold to Moreno's Trans Pacific Cable Company.

The subsidy to the China line of steamers was carried by the lavish use of money; but it was never paid. Appropriations were passed for the education of Hawaiian youths abroad, and for the coronation of the King and Queen.

At last on the 4th of August, Gibson brought in a motion of "want of confidence," which, after a lengthy debate, was defeated by the decisive vote of 32 to 10. On the 14th, the King prorogued the Legislature at noon, and about an hour later dismissed his ministers without a word of explanation, and appointed Moreno, Premier and Minister of Foreign Affairs; J. E. Bush, Minister of the Interior; W. C. Jones, Attorney-General; and Rev. M. Kuaea, Minister of Finance.

FALL OF THE MORENO MINISTRY.

Moreno was generally detested by the foreign community, and the announcement of his appointment created intense excitement.

For the first time the discordant elements of the foreign community were united, and they were supported by a large proportion p6 of the natives. The three highest and most influential chiefs — Queen Dowager Emma, Ruth Keelikolani and Bernice Pauahi Bishop — joined in condemning the King's course. Two mass meetings were held at the Kaumakapili church, and a smaller one of foreigners at the old Bethel church, to protest against the coup d'etat. The diplomatic representatives of the United States, England and France — General Comly, Major Wodehouse and M. Ratard — raised their respective flags over their legations, and declared that they would hold no further official intercourse with the Hawaiian Government as long as Moreno should be premier. On the side of the King, R. W. Wilcox, Nawahi and others harangued the natives, appealing to their jealousy of foreigners. The following manifesto is a sample:

"WAY-UP CELSO MORENO."

"To all true-born citizens of the country, greeting: We have with us one Celso Caesar Moreno, a naturalized and true Hawaiian. His great desire is the advancement of this country in wealth, and the salvation of this people, by placing the leading positions of Government in the hands of the Hawaiians for administration. The great desire of Moreno is to cast down foreigners from official positions and to put true Hawaiians in their places, because to them belongs the country. They should hold the Government and not strangers. Positions have been taken from Hawaiians and given to strangers. C. C. Moreno desires to throw down these foreigners and to elevate to high positions the people to whom belongs the land, i. e,, the red skins. This is the real cause of jealousy on the part of foreigners, viz., that Hawaiians shall be placed above them in all things in this well-beloved country, C. C. Moreno is the heart from whence will issue life to the real Hawaiians."

After four days of intense excitement, the King yielded to the storm. Moreno's resignation was announced on the 19th, and his place filled ad interim by J. E. Bush. On the 30th Moreno left for Europe, with three Hawaiian "youths" under his charge, viz., R. W. Wilcox, a member of the late Legislature, 26 years of age, Robert Boyd and James K. Booth. It was afterwards ascertained that he bore a secret commission as minister plenipotentiary and envoy extraordinary to all the great powers, as well as letters addressed to the Governments of the United States, England and France, demanding the recall of their representatives. A violent quarrel had broken out between him and his disappointed rival, Gibson, who purchased the P. C. Advertiser printing office with Government money September 1, and conducted that paper thenceforth as the King's organ.

Mr. W. L. Green was persuaded to accept the vacant place of minister of foreign affairs September 22. In a few days he discovered what had been done, and immediately notified the representatives of the three powers concerned of the insult that had been offered them.

A meeting was held at his office between the foreign representatives on the one side and himself and J. E. Bush on the p7 other, at which the letters in question were read. The result was that Mr. Green resigned and compelled the resignation of his colleagues.

THE GREEN-CARTER MINISTRY.

Mr. Claus Spreckels, who arrived September 5, took an active part in these events and in the formation of the new ministry, which consisted of W. L. Green, Minister of Foreign Affairs; H. A. P. Carter, Minister of the Interior; J. S. Walker, Minister of Finance, and W. N. Armstrong, Attorney-General.

Their first act was to annul Moreno's commission, and to send dispatches, which were telegraphed from San Francisco to Washington, London and Paris, disavowing the demands which he had sent. Moreno, however, proceeded on his journey and finally placed the Hawaiian youths, one in a military and two in a naval school in Italy.

THE KING'S TOUR AROUND THE WORLD.

The King immediately began to agitate his project of a trip around the world. As it was known that he was corresponding with Moreno, it was arranged that Mr. C. H. Judd should accompany him as Chamberlain, and Mr. W. N. Armstrong as Commissioner of Immigration. He was received with royal honors in Japan, Siam, and Johore. On the King's arrival in Naples, Moreno made an audacious attempt to take possession of His Majesty and dispense with his companions, but he met with more than his match in Armstrong. The royal party visited nearly all the capitals of Europe, where the King added a large number of decorations to his collection, and took particular note of military matters and court etiquette. An Austrian field battery which took his eye, afterwards cost this country nearly $20,000. During the King's absence his sister, Mrs. Dominis, styled Liliuokalani, acted as regent. He returned to Honolulu, October 29, 1881, where he had a magnificent reception, triumphal arches, torches blazing at noon-day, and extravagant adulation of every description.

TRIUMPH OF GIBSON.

During the King^s absence he had kept up a correspondence with his political workers at home, and after his return he produced another pamphlet in Hawaiian, advocating a ten-million loan. Gibson's paper had been filled with gross flattery of the King and of the natives, and had made the most of the smallpox epidemic of 1881 to excite the populace against the ministry.

Just before the election of 1882, a pamphlet appeared, containing a scathing exposure of his past career (especially in connection with the Mormon Church), backed by a mass of documentary evidence. Gibson's only reply was to point to his subsequent election by a large majority of the native voters of Honolulu. Only two other white men were elected on the islands that year. It was the first time that the race issue had superseded all other considerations with the native electorate.

SESSION OF 1882.

The Legislature of 1882 was one of the weakest and most corrupt that ever sat in Honolulu. At the opening of the session Minister Carter was absent in Portugal, negotiating a treaty with the Government of that country. It was soon evident that the Ministry did not control a majority of the House, but the King did. After an ineffectual attempt to quiet Gibson by offering him the Presidency of the Board of Health with a salary of $4000, they resigned May 19th, and Gibson became Premier.

His colleagues were J. E. Bush, lately of Moreno's cabinet; Simon Kaai, who drank himself to death; and Edward Preston, Attorney-General, who was really the mainstay of the Cabinet.

One of their first measures was an act to convey to Claus Spreckels the crown lands of Wailuku, containing some 24,000 acres, in order to compromise a claim which he held to an undivided share of the crown lands. He had purchased from Ruth Keelikolani, for the sum of $10,000, all the interest which she might have had in the crown lands as being the half-sister of Kamehameha IV., who died intestate. Her claim had been ignored in the decision of the Supreme Court and the Act of 1865, which constituted the crown lands. Instead of testing her right by a suit before the Supreme Court, the Ministry thought it best to accept the above compromise, and carried it through the Legislature.

The prohibition against furnishing intoxicating liquor to natives was repealed at this session, and the consequences to the race have been disastrous. The ten-million loan bill was again introduced, but was shelved in committee and a two-million loan act substituted for it. The appropriation bill was swelled to double the estimated receipts of the Government, including $30,000 for coronation expenses, $80,000 for Hawaiian youths in foreign countries, $10,000 for a Board of Genealogy, besides large sums for the military, foreign embassies, the palace, etc.

At the last moment a bill was rushed through, giving the King sole power to appoint district justices, through his creatures, the governors, which had formerly been done only "by and with the advice of the Justices of the Supreme Court." This was another step toward absolutism. Meanwhile Gibson defended the King'e right to be an active politician, and called him "the first Hawaiian King with the brains and heart of a statesman."

At the same time it was understood that Claus Spreckels backed the Gibson ministry and made them advances under the Loan Act.

THE CORONATION.

Kalakaua had always felt dissatisfied with the manner in which he had been sworn in as a King. He was also tired of being reminded that he was not a King by birth, but only by election. To remedy this defect he determined to have p9 the ceremony performed over again in as imposing a manner as possible. Three years were spent in preparations for the great event and invitations were sent to all rulers and potentates on earth to be present in person or by proxy on the occasion. Japan sent a commissioner, while England, France and the United States were represented by ships of war. The ceremony took place February 12, 1883, nine years after Kalakaua's inauguration. Most of the regalia had been ordered from London, viz., two crowns, a scepter, ring and sword, while the royal feather mantle, tabu stick and kahili or plumed staff, were native insignia of rank.

A pavilion was built for the occasion, as well as a temporary amphitheatre for the spectators. The Chief Justice administered the oath of office and invested the King with the various insignia. This ceremony was boycotted by the high chiefs, Queen Emma, Ruth Keelikolani and Mrs. Bernice Pauahi Bishop, and by a large part of the foreign community, as an expensive and useless pageant intended to aid the King's political schemes to make himself an absolute monarch. The coronation was followed by feasts, a regatta and races, and by a series of nightly hula hulas, i. e., heathen dances, accompanied by appropriate songs. The printer of the coronation hula programme, which contained the subjects and first lines of these songs, was prosecuted and fined by the court on account of their gross and incredible obscenity.

EMBASSIES, ETC.

During this year Mr. J. M. Kapena was sent as Envoy Extraordinary to Japan, while Mr. C. P. Iaukea, with H. Poor as secretary, was sent to attend the coronation of the Czar Alexander III. at Moscow, and afterwards on a mission to Paris, Rome, Belgrade, Calcutta and Japan, on his way around the world.

Kalakaua was no longer satisfied with being merely a King of Hawaii, but aspired to what Gibson termed the "Primacy of the Pacific." Captain Tripp and F. L. Clarke were sent as royal commissioners to the Gilbert Islands and New Hebrides to prepare the way for a Hawaiian protectorate; and a parody on the "Monroe doctrine" was put forth in a grandiloquent protest addressed to all the great powers by Mr. Gibson, warning them against any further annexation of the islands in the Pacific Ocean, and claiming for Hawaii the exclusive right "to assist them in improving their political and social condition," i. e., a virtual protectorate of the other groups.

THE HAWAIIAN COINAGE.

The King was now impatient to have his "image and superscription "on the coinage of the realm, to add to his dignity as an independent monarch. As no appropriation had been made for this purpose, recourse was had to the recognized "power behind the throne." Mr. Claus Spreckels purchased the bullion, and arrangements were made with the San Francisco p10 mint for the coinage of silver dollars and fractions of a dollar, to the amount of one million dollars' worth, to be of identical weight and fineness with the like coins of the United States. The intrinsic value of the silver dollar at that time was about 84 cents. It was intended, however, to exchange this silver for gold bonds at par under the Loan Act of 1882. On the arrival of the first installment of the coin, the matter was brought before the Supreme Court by Messrs. Dole, Castle and W. O. Smith, After a full hearing of the case, the court decided that these bonds could not legally be placed except for par value in gold coin of the United States, and issued an injunction to that effect on the Minister of Finance, December 14, 1883. The Privy Council was then convened, and declared these coins to be of the legal value expressed on their face, subject to the legal-tender act, and they were gradually put into circulation. A profit of $150,000 is said to have been made on this transaction.

THE FIRST RECONSTRUCTION OF

THE GIBSON CABINET, 1883.

Mr. Gibson's first Cabinet went to pieces in little over a year. Simon Kaai was compelled to resign in February, 1883, from "chronic inebriety," and was succeeded by J. M. Kapena. Mr. Peterson resigned the following May from disgust at the King's personal intermeddling with the administration, and in July Mr. Bush resigned in conscequence of a falling out with Mr. Gibson. For some time "the secretary stood alone," being at once Minister of Foreign Affairs, Attorney-General and Minister of the Interior ad interim; besides being a President of the Board of Health, President of the Board of Education and member of the Board of Immigration, with nearly the whole foreign community opposed to him. The price of Government bonds had fallen to 75 per cent, with no takers, and the treasury was nearly empty. At this juncture (August 6) when a change of Ministry was looked for, Mr. C. T. Gulick was persuaded to take the portfolio of the Interior, and a small loan was obtained from his friends. Then to the surprise of the public, Colonel Claus Spreckels decided to support the Gibson Cabinet, which was soon after completed by the accession of Mr. Paul Neumann.

THE LEGISLATURE OF 1884.

Since 1882 a considerable reaction had taken place among the natives, who resented the cession of Wailuku to Spreckels, and felt a profound distrust of Gibson. In spite of the war cry "Hawaii for Hawaiians," and the lavish use of Government patronage, the Palace party was defeated in the elections generally, although it held Honolulu, its stronghold. Among the Reform members that session were Messrs. Dole, Rowell, Smith, Hitchcock, the three brothers, Godfrey, Cecil and Frank Brown, Kauhane, Kalua, Nawahi, and the late Pilipo, of honored memory.

At the opening of the session the Reform party elected the speaker of the house, and controlled the organization of the committees.

The report of the Finance committee was the most damaging exposure ever made to a Hawaiian Legislature. A resolution of "want of confidence" was barely defeated (June 28) by the four Ministers themselves voting on it.

THE SPEECKELS' BANK CHARTER.

An act to establish a national bank had been drawn up for Colonel Spreckels by a well-known law firm in San Francisco, and brought down to Honolulu by ex-Governor Lowe. After "seeing" the King, and the usual methods in vogue at Sacramento, the ex-Governor returned to San Francisco, boasting that "he had the Hawaiian Legislature in his pocket." But as soon as the bill had been printed and carefully examined, a storm of opposition broke out. It provided for the issue of a million dollars worth of paper money, backed by an equal amount of Government bonds deposited as security. The notes might be redeemed in either silver or gold. There was no clause requiring quarterly or semi-annual reports of the state of the bank. Nor was a minimum fixed of the amount of cash to be reserved in the bank. In fact, most of the safeguards of the American national banking system were omitted. Its notes were to be legal tender except for customs dues. It was empowered to own steamship lines and railroads, and carry on mercantile business, without paying license fees. It was no doubt intended to monopolize or control all transportation within the Kingdom, as well as the importing business from the United States.

The charter was riddled both in the house and in the chamber of commerce, and indignation meetings of citizens were held until the King was alarmed, and finally it was killed on the second reading by an overwhelming majority. On hearing of the result the sugar king took the first steamer for Honolulu, and on his arrival "the air was blue — full of strange oaths, and many fresh and new." On second thought, however, and after friendly discussion, he accepted the situation, and a fair general banking law was passed, providing for banks of deposit and exchange, but not of issue.

THE LOTTERY BILL, ETC.

At the same session a lottery bill was introduced by certain agents of the Louisiana company. It offered to pay all the expenses of the leper settlement for a license to carry on its nefarious business, besides offering private inducements to venal legislators. In defiance of the public indignation, shown by mass meetings, petitions, etc., the bill was forced through its second reading, but was stopped at that stage and withdrawn, as is claimed, by Col. Spreckels' personal influence with the King.

Kalakaua's famous "Report of the Board of Genealogy" was published at this session. An opium license bill was killed, as well as an eight-million dollar loan bill, while a number of excellent laws were passed. Among these were the currency act and Dole's homestead law. The true friends of the native race had reason to rejoice that so much evil had been prevented.

PRACTICAL POLITICS UNDER GIBSON.

During the next few years the country suffered from a peculiarly degrading kind of despotism. I do not refer to the King's personal immorality, nor to his systematic efforts to debauch and heathenize the natives to further his political ends.

The coalition in power defied public opinion and persistently endeavored to crush out or disarm all opposition, and to turn the Government into a political machine for the perpetuation of their power. For the first time in Hawaiian history faithful officers who held commissions from the Kamehamehas were summarily removed on suspicion of "not being in accord" with the cabinet, and their places generally filled by pliant tools. A marked preference was given to unknown adventurers and defaulters over natives and old residents. Even contracts (for building bridges, for instance) were given to firms in foreign countries.

The various branches of the civil service were made political machines, and even the Board of Education and Government Survey came near being sacrificed to "practical politics." All who would not bow the knee received the honorable sobriquet of " missionaries." The demoralizing effects of this regime, the sycophancy, hypocrisy and venality produced by it have been a curse to the country ever since. The Legislature of 1884 was half composed of office-holders, and wires were skillfully laid to carry the next election. Grog shops were now licensed in the country districts, to serve as rallying points for the "National Party." The Gibsonian papers constantly labored to foment race hatred among the natives and class jealousy among the whites.

Fortunately, one branch of the Government, the Supreme Court, still remained independent and outlived the Gibson regime.

THE ELECTION OF 1886.

The election of 1886 was the most corrupt one ever held in this Kingdom, and the last one held under the old regime. During the canvass the country districts were flooded with cheap gin, chiefly furnished by the King, who paid for it by franking other liquor through the Custom House free of duty, and thereby defrauding the Government of revenue amounting to $4749.85. (See report of Attorney-General for 1888, and the case of the King vs. G. W. Macfarlane, 1888.) Out of twenty-seven Government candidates twenty-three were office-holders, one a last year's tax assessor and one the Queen's secretary. A list of them is appended herewith. There was only one white man on the Government ticket, viz., the premier's son-in-law.

| DISTRICT | NAME | OFFICE |

| HAWAII | ||

| N. Kona | J. K. Nahale | Tax Collector. |

| S. Kona | D. H. Nahinu | Deputy Sheriff & Tax Collector. |

| Kau | Kaaeamoku | ........ |

| Puna | A. Kekoa | Tax Collector. |

| Hilo | Kaulukou | Sheriff. |

| Hilo | A. Pahia | Tax Collector. |

| Hamakua | Kaunamano | Tax Collector. |

| Kohala | Z. Kalai | District Judge. |

| MAUI | ||

| Lahaina | L. Aholo | Police Judge. |

| Lahaina | Kia Nahaolelua | Tax Collector. |

| Hana | S. W. Kaai | District Judge. |

| Makawao | J. Kamakele | Tax Collector. |

| Wailuku | G. Richardson | Road Sup'r. & Tax Collector. |

| Kaanapali | J. Kaukau | Deputy Sheriff & Tax Collector. |

| MOLOKAI & LANAI | ||

| ........ | Nakaleka | Tax Collector. |

| ........ | Kupihea | District Judge. |

| OAHU | ||

| Honolulu | F. H. Hayselden | Sec'y Bd. Health & Tax Coll'r. |

| Honolulu | James Keau | Poi Contractor. |

| Honolulu | Lilikalani | Queen's Secretary. |

| Honolulu | J. T. Baker | Capt. King's Guards. |

| Ewa & Waianae | J. P. Kama | District Judge. |

| Koolauloa | Kauahikaua | Tax Collector. |

| Koolaupoko | F. Kaulia | District Judge. |

| Waialua | J. Amara | Deputy Sheriff & Tax Collector. |

KAUAI | ||

| Hanalei | Palohau | Deputy Sheriff& Tax Collector. |

| Koloa | T. Kalaeone | ........ |

| Waimea | E. Kauai | District Judge. |

In order to prevent Pilipo's election, the King proceeded to his district of North Kona, taking with him a number of soldiers and attendants (Who voted at the election), besides numerous cases of liquor. He took an active part in the canvass, and succeeded in defeating Pilipo by a small majority. The King's interference with the election nearly provoked a riot, which was averted by Pilipo^s strenuous exertions. The matter was investigated by a legislative committee, whose report is on file. Mr. E. Kekoa, the member elected from Puna, was afterwards tried and convicted of gross violations of the election laws, but the House refused to declare his seat vacant.

Only ten Reform candidates were elected, viz.: Messrs. Cecil Brown, W. R. Castle, C. H. Dickey, S. B. Dole, J. Kauhane, A. Kauhi, J. W. Kalua, A. Paehaole, L. A. Thurston and J. Wight.

THE SESSION OF 1886.

The session of 1886 was a long one, and a vacation of two wreeks was taken, from July 26 until August 9, to allow the tax collectors in the Legislature to go home and nominally perform the duties of their office. About this time certain creditors to the Government in San Francisco brought pressure to bear upon the Ministry to cede or hypothecate the Honolulu waterworks and part of the wharves to a California company. The pressure became so great that the Ministers opposed to the project were requested by the King to resign, and a new Cabinet was formed June 30, 1886, consisting of p14 W. M. Gibson, Minister of the Interior; R. J. Creighton, a journalist, lately arrived from California, Minister of Foreign Affairs; J. T. Dare, another recent arrival, Attorney-General; and P. P. Kanoa, Minister of Finance, in place of J. Kapena, who had succumbed to the same failing that had destroyed Simon Kaai.

The two new members of the Cabinet were respectable gentlemen, but soon found themselves in a false position.

THE OPIUM BILL.

An opium-license bill was introduced towards the end of the session by Kaunamano, one of the King's tools, and after a long debate carried over the votes of the Ministry by a bare majority. It provided that a license for four years should be granted to "some one applying therefor" by the Minister of the Interior, with the consent of the King, for $30,000 per annum. The object of this provision was plainly seen at the time, and its after consequences were destined to be disastrous to its author. Mr. Dole proposed an amendment that the license be sold at public auction at an upset price of $30,000, which, however, was defeated by a majority of one, only one white man, F. H. Hayselden, voting with the majority.

Another act was passed to create a so-called "Hawaiian Board of Health," consisting of five kahunas, appointed by the King, with power to issue certificates to native kahunas to practice native medicine."

THE LONDON LOAN.

The King had been convinced that, for the present, he must forego his pet scheme of a ten-million loan. A two-million loan bill, however, was brought in early in the session, with the view of obtaining the money in San Francisco. The subject was dropped for a time, then revived again, and the bill finally passed September 1.

Meanwhile, the idea of obtaining a loan in London was suggested to the King by Mr. A. Hoffnung, of that city, whose firm had carried on the Portuguese immigration. The proposal pleased the King, who considered that creditors at so great a distance would not be likely to trouble themselves much about the internal politics of this little Kingdom. Mr. H. R. Armstrong, of the firm of Skinner & Co., London, visited Honolulu to further the project, which was engineered by Mr. G. W. Macfarlane in the Legislature.

Two parties were now developed in that body, viz., the Spreckels' party, led by the Ministry, and the King's party, which favored the London loan. The small knot of independent members held the balance of power.

The two contending parties brought in two sets of conflicting amendments to the loan act, of which it is not necessary to give the details. As Kaulukou put it, "the amendment of the Attorney-General provides that if they want to borrow any money they must pay up Mr. Spreckels first. He understood that the Government owed Mr. Spreckels $600,000 or p15 $700,000. He has lent them money in the past, and were they prepared to say to him, "We have found new friends in England' — to give him a slap in the face?"

On the other side, Mr. J. T. Baker "was tired of hearing a certain gentleman spoken of as a second King. As this amendment was in the interest of that gentleman he voted against it." Allusions were also made to the reports that the waterworks were going to he pledged to him. When the decisive moment arrived, the independents cast their votes with the King's party, defeating the ministry by 23 votes to 14. The result was that the cabinet resigned that night, after which Gibson went on his knees to the King and begged to be reappointed.

The next morning, October 14, to the surprise of every one and to the disgust of his kite allies, Gibson reappeared in the house as premier, with three native colleagues, viz., Aholo, Kanoa and Kaulukon. But from this time on he had no real power, as he had neither moral nor financial backing. The hehn of state had slipped from his hands. Mr. Spreckels called on the King, returned all his decorations, and shook off the dust from his feet. The Legislature appropriated 1100,000 for a gunboat and $15,00n to celebrate the King's fiftieth birthday.

In this brief sketch it is imposible to give any idea of the utter want of honor and decency that characterized the proceedings of the Legislature of 1886.

The appropriation bill footed up $3,856,755.50, while the estimated receipts were $2,336,870.42.

THE SEQUEL OF THE LONDON LOAN.

From the report of the Minister of Finance for 1888 we learn that Mr. H. R. Armstrong, who had come to Honolulu as the agent of the London syndicate, was appointed agent of the Hawaiian Government to float the loan. He was also appointed Hawaiian Consul-General for Great Britain, while Mr. A. Hoffnung, previously referred to, was made Charge d'Affaires.

In the same report we find that the amount borrowed under the loan act of 1886 in Honolulu was $771,800 and in London $980,000. Of the former amount $630,000 was used to extinguish the debt owed to Col. Spreckels. By the terms of the loan act the London syndicate was entitled to 5 per cent, of the proceeds of the bonds which they disposed of, as their commission for guaranteeing them at 98 per cent. But it appears that in addition to this amount £15,000, or about $75,000, was illegally detained by them and has never been accounted for. The Legislature of 1888 appropriated the sum of $5,000 to defray the expenses of a lawsuit against the financial agents, to recover the $75,000 thus fraudulently retained. The matter was placed in the hands of Col. J. T. Griffin, who advised the Government that it was not expedient to prosecute the case. The $75,000 has therefore been entered on the books of the treasury department as a dead loss. Since then Mr. H. R. Armstrong's name has ceased to appear in the Government directory among those of the Consuls-General.

ROYAL MISRULE.

As before stated, the King now acted as his own prime minister, employing Gibson to execute his schemes and defend his follies. For the next eight months he rapidly went from bad to worse. After remaining one month in the cabinet Mr. Kaulukou was transferred to the Marshal's office, while Mr. Antone Rosa was appointed Attorney-General in his place and J. M. Kapena made Collector-General. The limits of this brief sketch forbid any attempt to recount the political grievances of this period. Among the lesser scandals were the sale of offices, the defrauding of the customs revenue by abuse of the royal privilege, the illegal leasing of lands in Kona and Kau to the King without putting them up to auction, the sale of exemptions to lepers, the gross neglect of the roads, and misapplication of road money, particularly of the Queen street appropriation.

Efforts to revive heathenism were now redoubled under the pretense of cultivating "national" feeling. Kahunas were assembled from the other islands as the King's birthday approached, and "night was made hideous" with the sound of the hula drum and the blowing of conchs in the palace yard. A foreign fortune teller by the name of Rosenberg acquired great influence with the King.

THE HALE NAUA, ALIAS TEMPLE OF SCIENCE,

ALIAS BALL OF TWINE SOCIETY.

This was founded September 24, 1886. A charter for it was obtained by the King from the Privy Council, not without difficulty, on account of the suspicion that was felt in regard to its character and objects. According to its constitution it was founded forty quadrillions of years after the foundation of the world, and twenty-four thousand seven hundred and fifty years from Lailai, the first woman.

Its by-laws are a travesty of Masonry, mingled with pagan rites. The Sovereign is styled Iku Hai; the secretary, Iku Lani; the treasurer, Iku Nuu. Besides these were the keeper of the sacred fire, the anointer with oil, the almoner, etc. Every candidate had to provide an "oracle," a kauwila wand, a ball of olona twine, a dried fish, a taro root, etc. Every member or "mamo" was invested with a yellow malo or pau (apron) and a feather cape. The furniture of the hall comprised three drums, two kahilis or feathered staffs, and two puloulous or tabu sticks.

So far as the secret proceedings and objects of the society have transpired, it appears to have been intended partly as an agency for the revival of heathenism, partly to pander to vice, and indirecly, to serve as a political machine. Enough leaked out to intensify the general disgust that was felt at the debasing influence of the palace.

KALAKAUA'S JUBILEE.

The sum of $15,000 had been appropriated by the Legislature of 1886 towards the expenses of the celebration of His Majesty's fiftieth birthday, which occurred November 16, 1886.

Extensive preparations were made to celebrate this memorable occasion, and all office holders were given to understand that every one of them was expected to "hookupu" or make a present corresponding to his station. At midnight preceding the auspicious day a salute was fired and bonfires were lighted on Punchbowl Hill, rockets were sent up, and all the bells in the city set ringing.

The reception began at 6 A. M. Premier Gibson had already presented the King with a pair of elephant tusks mounted on a koa stand with the inscription: "The horns of the righteous shall be exalted." The Honolulu police marched in and presented the King with a book on a velvet cushion containing a bank check for $570. The Government physicians, headed by F. H. Hayselden, Secretary of the Board of Health, presented a silver box containing $1,000 in twenty dollar gold pieces. The Custom House clerks offered a costly gold-headed cane. All officials paid tribute in some shape. Several native benevolent societies marched in procession, for the most part bearing koa calabashes. The school children, the fishermen and any other natives marched through the throne room, dropping their contributions into a box. It is estimated that the presents amounted in value to $8,000 or $10,000.

In consequence of the Hale Naua scandal scarcely any white ladies were seen at this reception. In the evening the Palace was illuminated with electric lights, and a torchlight parade of the Fire Department took place, followed by fireworks at the Palace.

On the 20th, the public were amused by a so-called historical procession, consisting chiefly of canoes and boats carried on drays, containing natives in ancient costume, personating warriors and fishermen, mermaids draped with sea moss, hula dancers, etc., which passed through the streets to the Palace. Here the notorious Hale Naua or "Kilokilo" society had mustered, wearing yellow malos and paus or aprons over their clothes, and marched around the Palace, over which the yellow flag of their order was flying.

On the 28d a luau or native feast was served in an extensive lanai or shed in the Palace grounds, where 1500 people are said to have been entertained. This was followed by a jubilee ball in the Palace on the 25th. The series of entertainments was closed by the exhibition of a set of "historical tableaux" of the olden time at the Opera House, concluding with a hulahula dance, which gave offense to most of the audience. No programme was published this time of the nightly hulahulas performed at the Palace.

THE SAMOAN EMBASSY.

In pursuance of the policy announced in Gibson's famous protest to the other great powers, and in order to advance Hawaii's claim to the "primacy of the Pacific," Hon. J. E. Bush was commissioned on the 23d of December, 1886, as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the King of Samoa and the King of Tonga, and High Commissioner to p18 the other independent chiefs and peoples of Polynesia. He was accompanied by Mr. H. Poor, as Secretary of Legation, and J. D. Strong, as artist and collector for the Government museum. They arrived at Apia, January 3d, 1887, and were cordially received by King Malietoa on the 7th, when they drank kava with him and presented him with the Grand Cross of the Order of Oceana. Afterwards, at a more private interview, Bush intimated to Malietoa that he might expect a salary of $5,000 or $6,000 under a Hawaiian protectorate. A house was built for the Legation at the expense of the Hawaiian Government.

A convention was concluded February 17th, between King Malietoa and the Hawaiian Envoy, by which both parties bound themselves "to enter into a political confederation," which was duly ratified by Kalakaua and Gibson, "subject to the existing treaty obligations of Samoa," March 20th, 1887.

"The signature was celebrated," says Robert Louis Stevenson, "in the new house of the Hawaiian Embassy with some original ceremonies. Malietoa came attended by his ministers, several hundred chiefs (Bush says 60), two guards and six policemen. Laupepa (Malietoa), always decent, withdrew at an early hour; by those that remained all decency appears to have been forgotten, and day found the house carpeted with slumbering grandees, who had to be roused, doctored with coffee and sent home. * * * Laupepa remarked to one of the Embassy, 'If you come here to teach my people to drink, I wish you had stayed away.'" The rebuke was without effect, for still worse stories are told of the drunken orgies that afterwards disgraced the Hawaiian Embassy.

THE KAIMILOA.

About this time Mr. J. T. Arundel, an Englishman, engaged in the copra trade, visited Honolulu in his steamer, the Explorer, a vessel of 170 tons, which had been employed in plying between his trading stations. The King who was impatient to start his new navy, to maintain "Hawaiian primacy," had put the Reformatory School under the charge of Captain G. E. Jackson, a retired navigating lieutenant in the British navy, with the view of turning that institution into a naval training school. The old Explorer was purchased for $20,000, and renamed the Kaimiloa. She was then altered and fitted out as a man-of-war at an expense of about $50,000, put into commission March 28th, and placed under the command of Captain Jackson. The crew was mainly composed of boys from the Reformatory School, whose conduct, as well as that of their officers, was disgraceful in the extreme.

The Kaimiloa sailed for Samoa, May 18th, 1887. On the preceding evening a drunken row had taken place on board, for which three of the officers were summarily dismissed. The after history of the expedition was in keeping with its beginning. As Stevenson relates: "The Kaimiloa was from the first a scene of disaster and dilapidation, the stores were sold; the crew revolted; for a great part of a night she was in the p19 hands of mutineers, and the Secretary lay bound upon the deck.

On one occasion the Kaimiloa was employed to carry the Hawaiian Embassy to Atua, for a conference with Mataafa, who had remained neutral, but she was followed and watched by the German corvette Adler. "Mataafa was no sooner set down with the Embassy than he was summoned and ordered on board by two German officers."

Another well-laid plan to detach the rebel leader, Tamasese, from his German "protectors" was foiled by the vigilance of Captain Brandeis. At length Bismarck himself was incensed, and caused a warning to be sent from Washington to Gibson, in consequence of which Minister Bush was recalled July 7th, 1887. Mr. Poor was instructed to dispose of the Legation property as soon as possible, and to send home the attaches, the Government curios, etc., by the Kaimiloa, which arrived in Honolulu, September 23d. She was promptly dismantled, and afterwards sold at auction, bringing the paltry sum of $2,800. Her new owners found her a failure as an inter-island steamer, and she is now laid up in the "naval row."

THE AKI CASE OR OPIUM SCANDAL.

The facts of this case were stated in the affidavit of Aki, published May 31st, 1887, and those of Wong Leong, J. B. Walker and Nahora Hipa, published June 28th, 1887, as well as in the decision of Judge Preston in the case of Loo Ngawk et al. Executors of the will of T. Aki vs. A. J. Cartwright et al., trustees of the King (Haw. Rep., Vol. vii., p 401).

I have already spoken of the opium license law, which was carried by the royalist party in the Legislature of 1886, and signed by the King in spite of the vigorous protests from all classes of the community. As this law had been saddled with amendments, which rendered it nearly unworkable, a set of regulations was published October 15, 1886, providing for the issue of permits to purchase or use opium by the Marshal, who was to retain half the fee and the Government the other half.

The main facts of the case, as proved before the court, are as follows: Early in November, 1886, one, Junius Kaae, a palace parasite, informed a Chinese rice-planter named Tong Kee, alias Aki, that he could have the opium license granted to him if he would pay the sum of $60,000 to the King's private purse, but that he must be in haste because other parties were bidding for the privilege. With some difficulty Aki raised the money, and secretly paid it to Kaae and the King in three instalments between December 3d and December 8th, 1886. Soon afterwards Kaae called on Aki and informed him that one, Kwong Sam Kee, had offered the King 175,000 for the license, and would certainly get it, unless Aki paid $15,000 more. Accordingly Aki borrowed the amount and gave it to the King personally on the 11th.

Shortly after this another Chinese syndicate, headed by Chung Lung, paid the King $80,000 for the same object, but p20 took the precaution to secure the license before handing over the money. Thereupon Aki, finding that he had lost both his money, and his license, divulged the whole affair, which was published in the Honolulu papers. He stopped the payment of a note at the bank for $4,000, making his loss $71,000. Meanwhile Junius Kaae was appointed to the responsible office of Registrar of Conveyances, which had become vacant by the death of the lamented Thomas Brown.

As was afterwards ascertained, the King had ordered a $100,000 gunboat from England, through Mr. G. W. Macfarlane, but the negotiations for it were broken off by the revolution.

On the 12th of April, 1887, Queen Kapiolani and the Princess Liliuokalani, accompanied by Messrs. C. P. Iaukea, J. H. Boyd, and J. O. Dominis, left for England to attend the celebration of the jubilee held upon the fiftieth anniversary of the accession of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. They returned on the 26th of July, 1887.

THE REVOLUTION OF 1887.

The exposure of the two opium bribes and the appointment of the King's accomplice in the crime as Registrar of Conveyances helped to bring matters to a crisis, and united nearly all tax-payers not merely against the King but against the system of government under which such iniquities could be perpetrated.

In the spring of 1887, a secret league had been formed in Honolulu, with branches on the other islands, for the purpose of putting an end to the prevailing misrule and extravagance, and of establishing a civilized government, responsible to the people through their representatives. Arms were imported, and rifle clubs sprang up all over the islands. In Honolulu a volunteer organization, known as the "Rifles," was increased in numbers, and brought to a high state of efficiency under the command of Col. V. V. Ashford. It is supposed that the league now numbered from 800 to 1,000 men, while its objects had the sympathy of the great majority of the community. It was at first expected that monarchy would then be abolished, and a republican constitution was drawn up.

As the time for action approached, the resident citizens of the United States, Great Britain and Germany addressed memorials to their respective governments, through their representatives, declaring the condition of affairs to be intolerable. As is the case in all such movements, the league was composed of average men, actuated by a variety of motives, but all agreed in their main object. Fortunately, the "spoils wing" of the party failed eventually to capture either branch of the Government, upon which a number of them joined the old Gibsonian party and became bitter enemies of reform.

Some members of the league, including Col. Ashford, were in favor of a sudden attack upon the Palace, but this advice was overruled, and it was decided to first hold a public mass meeting, to state their grievances, and to present specific p21 demands to the King. Accordingly, on the afternoon of the 30th of June, 1887, all business in Honolulu was suspended, and an immense meeting was held in the armory , on Beretania Street, composed of all classes, creeds, and nationalities, but united in sentiment as never before or since. The meeting was guarded by a battalion of the Rifles fully armed. A set of resolutions was passed unanimously, declaring that the Government had "ceased through incompetency and corruption to perform the functions and to afford the protection to personal and property rights for which all governments exist," and demanding of the King the dismissal of his cabinet, the restitution of the $71,000 received as a bribe from Aki, the dismissal of Junius Kaae from the land office, and a pledge that the King would no longer interfere in politics.

A committee of thirteen was sent to wait on His Majesty with these demands. His troops had mostly deserted him, and the native populace seemed quite indifferent to his fate. He called in the representatives of the United States, Great Britain, France, and Portugal, to whom he offered to transfer his powders as King. This they refused, but advised him to lose no time in forming a new cabinet and signing a new constitution. Accordingly he sent a written reply the next day, which virtually conceded every point demanded. The new cabinet, consisting of Godfrey Brown, Minister of Foreign Affairs; L. A. Thurston, Minister of the Interior; W. L. Green, Minister of Finance; and C. W. Ashford, Attorney-General, was sworn in on the same day, July 1st, 1887,

THE CONSTITUTION OF 1887.

As the King had yielded, the republican constitution was dropped, and the constitution of 1864 revised in such a way as to secure two principal objects, viz., to put an end to autocratic rule by making the Ministers responsible only to the people through the Legislature and to widen the suffrage by extending it to foreigners, who till then had been practically debarred from naturalization. I have given the details in another paper.

Mr. Gibson was arrested July 1st, but was allowed to leave on the 5th by a sailing vessel for San Francisco. Threats of lynching had been made by some young hot heads, but fortunately no acts of violence or revenge tarnished the revolution of 1887.

An election for members of the Legislature was ordered to he held September 12th, and regulations were issued by the new ministry, which did away with many abuses, and secured the fairest election that had been held in the islands for twenty years. The result was an overwhelming victory for the Reform party, which was a virtual ratification of the new constitution. During the next three years, in spite of the bitter hostility and intrigues of the King, the continual agitation by demagogues, and repeated conspiracies, the country prospered under the most efficient administration that it had ever known.

FINAL SETTLEMENT OF THE AKI CASE.

It has been seen that on the 30th of Jane, 1887, Kalakaua promised in writing that he would "cause restitution to be made" of the $71,000 which he had obtained from Aki, under a promise that he (Aki) should receive the license to sell opium, as provided by the Act of 1886.

The Reform cabinet urged the King to settle this claim before the meeting of the Legislature, and it was arranged that the revenues from the Crown lands should be appropriated to that object. When, however, they ascertained that his debts amounted to more than $250,000 they advised the King to make an assignment in trust for the payment of all claims pro rata. Accordingly, a trust deed was executed November 21, 1887, assigning all the Crown land revenues and most of the King's private estate to three trustees for the said purpose, on condition that the complainant would bring no petition or bills before the Legislature, then in session.

Some three months later these trustees refused to approve or pay the Aki claim, on which Aki's executors brought suit against them in the Supreme Court.

After a full hearing of the evidence. Judge Preston decided that the plea of the defendants that the transaction between Aki and the King was illegal could not be entertained, as by the constitution the King "could do no wrong," and "could not be sued or held to account in any court of the Kingdom." Futhermore, as the claimants had agreed to forbear presenting their claim before the Legislature in consideration of the execution of the trust deed, the full court ordered their claim to be paid pro rata with the other approved claims.

Footnote:

The statement furnished Col. Blount ends with this Chapter. The story will now be continued to the end of the year 1893.

The preceding narrative ended with the revolution of 1887, which was intended to put an end to personal rule in the Hawaiian Islands, by making the ministry responsible to the people through the legislature, by taking the power of appointing the Upper House out of the hands of the Sovereign, and by making office-holders ineligible to the legislature.

The remaining three years and a half of Kalakaua's reign teemed with intrigues and conspiracies to restore autocratic rule. The Reform party, as has been stated, gained an overwhelming majority of seats in the legislature of 1887, and had full control of the government until the legislative session of 1890.

During the special session, held in November, 1887, a contest arose between the King and the legislature in regard to the veto power, which at one time threatened the public peace. The question whether under the new constitution the King could p23 exercise a personal veto against the advice of his ministers or not, was finally decided by the Supreme Court in favor of the Crown. Judge Dole dissenting.

During the succeeding session of 1888 the King vetoed a number of bills, which were all passed over his veto, by a two-thirds vote, with the exception of a bill to subsidize an experimental coffee plantation.

CONSPIRACIES.

The King's sister, the then Princess Liliuokalani, on her return from England, had charged her brother with cowardice, for signing the constitution of 1887, and was known to be in favor of the old system of irresponsible personal government. For instruments she had not far to seek. Two of the Hawaiian youths whom Moreno had placed in military school in Italy, as before stated, had been recalled towards the end of 1887.

They had been led to expect high positions from the Gibson Government, and their disappointment was extreme, when their claims were ignored. Hence they were easily induced to lead a conspiracy, which had for its object the abrogation of the constitution of 1887, and the restoration of the old regime.

They endeavored to form a secret league, and held meetings to inflame the native mind, but without much success at first.

It is said that the Household Troops were won over, and that the three chief conspirators, on one occasion, detained the King in one of the tower rooms in the Palace, and tried to intimidate him into signing his abdication in favor of his sister.

The King parleyed with them to gain time, and the affair soon came to the ears of the ministry, who had the conspirators examined, one by one, and their statements taken down. A mass of evidence was collected, which, however, was not used against them; and the leader, Mr. R. W. Wilcox, was allowed to go to California, where he remained about a year, biding his time.

Meanwhile, a secret organization was being formed throughout the islands, and after some progress had been made, Mr. Wilcox was sent for. He returned to Honolulu in April, 1889, formed a rifle club, and began to make preparations for a counter revolution.

The meetings of the league were held in a house belonging to the Princess Liliuokalani. At the subsequent trial it was proved by the defense that the King had latterly come to an understanding with the conspirators, whose object was to restore autocratic rule.

Before light, on the morning of July 30th, 1889, Mr. Wilcox with about one hundred and fifty armed followers marched from the Princess Liliuokalani's residence in Kapalama and occupied the Government buildings and the palace grounds. No declaration of any kind was made, as they expected the p24 King, who had spent the night at a cottage near the seaside, to come up and proclaim the old constitution of 1864. The Household troops in the barracks remained neutral, and the palace was held against the insurgents by Lieut. Robert Parker, with thirty men by the King's orders. The King, who did not fully trust the conspirators, retired to his boat-house in the harbor to await results. Meanwhile the volunteer rifle-men promptly turned out, and many other citizens took up arms for the Government. Patrols were set about day-light, and a cordon formed later on, so that the insurgents were isolated from the populace outside. At the request of the United States Minister, Mr. Merrill, a body of marines was landed and marched up to the Legation, on the hotel premises, where they remained during the day. The insurgents brought over four field-pieces and ammunition from the barracks, and placed them around the palace.

The Ministry drew up a written summons to them to surrender, which was served on them at the front palace gate, by the Hon. S. M. Damon, but they refused to receive it. A conflict immediately commenced between them with three of their field pieces and the Government sharpshooters, who had occupied the Opera House and some other buildings commanding the palace grounds. The result was that their guns were soon silenced, and they were driven with loss into a wooden building in the palace grounds, called the "Bungalow," where they were besieged during the afternoon. Towards night a heavy rifle fire was opened upon them from all sides, and the roof of the "Bungalow" Burst in by giant powder bombs, which forced them to surrender.

Unfortunately, this was by no means a bloodless affair, as seven of Wilcox's deluded followers were killed and about a dozen wounded. It was afterwards learned that 10,000 rounds of ammunition had been loaned by the U. S. S. Adams during the day to the Hawaiian Government.

The chief conspirators were afterwards put on trial for treason, with the result that Loomens, a Belgian artilleryman, was found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment for life, while Mr. R. W. Wilcox was acquitted by a native jury, on the theory that what he had done was by and with the King's consent. He now became a popular idol, and had unfounded influence over the Honolulu natives for a time. The Princess Liliuokalani, however, disowned him, and denied all knowledge of the conspiracy. This deplorable affair was made the most of by demagogues to intensify race hatred. The license allowed the native press was almost incredible.

THE PROPOSED COMMERCIAL TREATY.

A project of a new commercial treaty with the United States was drawn up in the fall of 1889 by the Ministry in conjunction with Hon. H. A. P. Carter. Its terms provided for complete free trade between the two countries, the perpetual cession of Pearl Harbor to the United States, and a guarantee of the independence of the Kingdom by that power. In p25 consideration of this guarantee, the Hawaiian Government was to bind itself to make no treaty with any foreign power without the knowledge of the Government of the United States.

By working on the King's suspicions, Mr. C. W. Ashford, the Attorney-General, induced the King to refuse to sign the preliminary draft of this treaty. The other members of the Cabinet invited him to resign, which he declined to do.

The question having been brought before the Supreme Court, it decided that the King under the Constitution was bound by the advice of a majority of his Cabinet. But the Attorney-General advised the King that this was only an ex parte decision, and encouraged him to defy the court. A copy of the proposed treaty, (including an article which had been rejected by the Cabinet, and which would have authorized the landing of United States troops in certain emergencies), was secretly furnished by the King to a native newspaper for publication, and the party cry was raised that the ministry was "selling the country" to the United States.

THE SESSION OF 1890.

On account of the circumstances mentioned above, and of dissensions in the Reform party, the combined elements in opposition elected a majority of the Legislature of 1890, and on the 13th of June, 1890, the Reform ministry went out of office on a close vote.

As the parties were so nearly balanced, a compromise cabinet, composed of conservative men, was apY)ointed June 17th, viz., Hons. John A. Cummins, Minister of Foreign Affairs; C, N. Spencer, Minister of the Interior; Godfrey Brown, Minister of Finance; A. P. Peterson, Attorney-GeneraL

The King at first tried to revive his old project of a ten-million loan bill for military and naval purposes, but met with no encouragement. He then published a pamphlet entitled "A Third Warning Voice," in which he urged the establishment of a large standing army.

Another project advocated by the reactionary papers and favored by the King, was that of calling a revolutionary convention, to be elected by the voters of the lower house, to frame a new constitution, in which the foreign element should be excluded from political power. With considerable difficulty, and by the exercise of much patience and tact, this dangerous measure was defeated, and certain constitutional amendments were passed through the preliminary stage. The most important of these was one lowering the property qualification required of electors for nobles. After a stormy session of five months, the Legislature adjourned Nov. 14th, 1890, without undoing the reforms made in 1887.

ACCENSION OF LILIOUKALANI.

In order to recruit his failing health, the King visited California in the United States cruiser Charleston, as the P26 guest of Admiral Brown, in November, 1890. He received the utmost kindness and hospitality, both in San Francisco and in Southern California. His strength, however, continued to fail in spite of the best medical attendance, and on the 20th of January, 1891, he breathed his last at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco. His remains were removed to the Charleston with impressive funeral ceremonies, and arrived at Honolulu January 29th, where the decorations for his welcome were changed into the emblems of mourning.

In spite of his grave faults as a ruler and as a man, he had been uniformly kind and courteous in private life, and there was sincere grief in Honolulu, when the news of his death arrived.

Serious apprehensions were now felt by many in view of the accession of his sister, Liliuokalani, which, however, were partially relieved by her promptly taking the oath, to maintain the constitution of 1887. Notwithstanding her despotic ideal of government, and her past record, there were not a few who hoped that she had enough good sense to understand her true interests, and to keep her oath to the constitution. They were destined to be disappointed. On the morning of her accession, Mr. S. M. Damon had an interview with her, in which he remarked that what was needed was a responsible ministry. "My ministry," she replied, "shall be responsible to me," and abruptly closed the interview. She had no sooner taken the oath, than a constitutional question was raised between her and the existing cabinet. On the one side, the cabinet claimed that under the constitution no power could remove them but the Legislature. On her side it was claimed that they were the late King's cabinet, and "died with the King." This dispute was referred to the Supreme Court, which decided in favor of the Queen, Judge McCully dissenting. This gave her an opportunity to exact conditions from the incoming ministers, and thus to secure control of the patronage of the Government.

The new cabinet appointed February 26th, 1891, consisted of Hons. S. Parker, Minister of Foreign Affairs; C. N. Spencer, reappointed Minister of the Interior; H. A. Widemann, minister of Finance; and W. A. Whiting, Attorney-General, The first condition exacted by the Queen of her appointees was that Mr. C. B. Wilson should be appointed Marshal of the Kingdom, with control of the entire police force of the islands. It was universally believed that he exercised as much influence on the administration of public affairs as any member of the cabinet. At the same time, grave charges were made against the administration of his own bureau. The Marshal's office was said to be the resort of disreputable characters, while opium joints and gambling dens multiplied and flourished. The marshal openly associated with such adventurers as Capt. Whaley, of the famous smuggling yacht Halcyon, and the Australian fugitives from justice, who visited Honolulu in the yacht Bengle.